Pushed or Pulled?

The paradox of how overprotection from the care system led me (and probably other children) into more dangerous situations.

Something is triggering about magnolia paint. Whenever I’ve asked why it’s used, I’m told that it is neutral and unoffensive. That it doesn’t insult anyone’s sense of taste. That no one has an opinion about magnolia. I do. The blandness. The offensive blandness. Not a blank canvas but one that states we don’t want personality here. It’s a nothing colour for nothing kids. Designed to sap the vibrant, dynamic, engaging energy out of the offensive kids it’s wrapped around. Almost every room in my teenage years had this spiteful paint. The oppression of any self-expression. Nobody cares about magnolia, was their mantra. Maybe this is why it is used in waiting rooms of social services, of police cells, of health clinics. Because nobody cares about the kids inside of them.

I thumped the small wire-glass window with a policeman’s knock to the seven-note ‘shave and a haircut’ rhythm. The health visitor jumped out of her skin. I didn’t want to be there as much as she probably didn’t want to see me, but this is one of the routines that no child outside the care system must endure. These small practical jokes were my way of making it tolerable. I had largely forgotten these even happened. Save one. I entered alongside the neglected scream of the door creaking and squeaking.

“Hiya, Matthew, take a seat.” She said.

I think I mumbled a reply.

“This is just a check-up to see how you’re getting on after your suicide attempt a couple of months ago.”

“What, suicide attempt? I’ve never tried to kill myself.”

“It says here on your records you did.”

How did I get there? How did I, after only being in the care system for under a year, descend into such chaos, and find myself sat in another magnolia room discussing a suicide attempt I had no recollection of? How did I end up in a place where I should never have been?

In 2021, the Children’s Commissioner released a report stating that children who enter residential care (children’s homes) as teenagers are “drawn into dangerous or criminal behaviour”. Ever since I started writing, I’ve learnt that the words a writer chooses to reveal much about their real thoughts. Whether they know it or not. In that report, which looks at the characteristics of the children entering the care system while trying to be on the side of children, in one word, they exposed their lingering institutional bias against those children. Drawn.

Drawn is to be attracted to. Pulled into the situation. That there is little the system could do at this point because the magnetic force is so strong. Drawn deletes any decision, removes any responsibility, cancels any culpability, frantically hits the backspace on any blame, cutting and pasting it all from the system to the dangerous situations, to the nefarious adults, to the innocent child. They – we – were not pulled, attracted to, or drawn into. We were pushed, repelled, forced into by the system. By lack of independence. By an unhealthy desire to overprotect. By suffocation. By not being able to learn how to have fun in a safe way. By being pushed away from stable friend groups. By being punished for their lack of trust.

In writing my memoir, I have pondered where it all started. Was my descent into chaos as invertible as the reports suggest, or could it have been prevented? One of the few benefits of being in care, and it is only a benefit in this situation, is that for all my time there, detailed notes were made by multiple ‘professionals’. I have over 15,000 pages detailing my life in fine detail.

Nothing is magnolia about reading my thirteen-year-old self, but it is triggering. As I dug and dug, looking for a start, memories that I felt were concrete turned to dust in one scroll of the screen. Part of the emotional reaction is just how biased, one-sided, and out-of-context, some of the observations are. This is something that deserves its own exploration and something I will dedicate a few Substack posts to.

I found two save points, which pushed me away from my stable friend group when I entered the care system. Two times, if the care workers and social workers behaved like normal parents, the decline might not have been as steep, or maybe not at all.

The first was not allowing me to go to an under-18 club night at the local theatre. Everyone I knew was going, all my friends were going, all the kids who could have overnight stays at their parents in my children’s home were going, and so I wanted to go. These events are essential to teaching boundaries and how to safely have fun while allowing children to feel independent. On the day of the club night, my social worker phoned my children’s home and asked the staff to inform me that she had decided I couldn’t go. Despite already having bought a ticket and was getting ready at a friend’s house and I was assured it wouldn’t be a problem. I was told my social worker wasn’t sure how safe it would be or whether I would encounter nefarious adults.

The second was wanting to stay overnight at a friend’s house, like I used to before I went into the system. The friend’s family passed all the intrusive background checks, but at the last minute, as last the time, the same social worker decided I couldn’t because she wasn’t sure about my safety.

To be treated like normal children. That’s all we want. For carers and social workers to behave like normal parents would. Any child who has been or is still in the care system will tell you this is all we want. To have the same freedoms as other children outside of the system. For the system to make decisions like any normal parent would. For the system to trust us, so we can learn how to be safe. Being safe, staying safe, keeping safe are skills learnt through experience. Not from being wrapped up in cotton wool.

The first law of teenagers is that they explore boundaries. Test them, push them, and, on occasion, break them. But where they are set is down to parenting. This can’t be avoided. They are always going to explore the limits. If they don’t get a chance to examine boundaries safely, they will end up doing it unsafely. This is the first law of teenagers.

“In April, you consumed a high number of Benzodiazepine tablets and ended up in hospital.” The health visitor explained. I had no idea what these tablets were, but I do remember a weekend when I went crazy on some medication, I stole from a house that me and my new friend group broke into.

“That was a crazy weekend, not a suicide attempt.”

“With these tablets, is there much difference? Are you ok with yourself now?”

I gradually fell out of my first friend group. I would no longer get invited to things. At this age, the strength of the bond between friends is equal to time spent together. I couldn’t give the time, so I fell out of orbit. Instead, I gravitated to people who could understand my situation or didn’t care. These people tended to be those who prayed on the vulnerabilities that came with me. I started to appear on the missing list, I engaged in crime, and I consumed unreasonable cocktails of drugs and alcohol. The situations, the people, and the behaviour, I now found myself in were incredibly dangerous. I shouldn’t have been there.

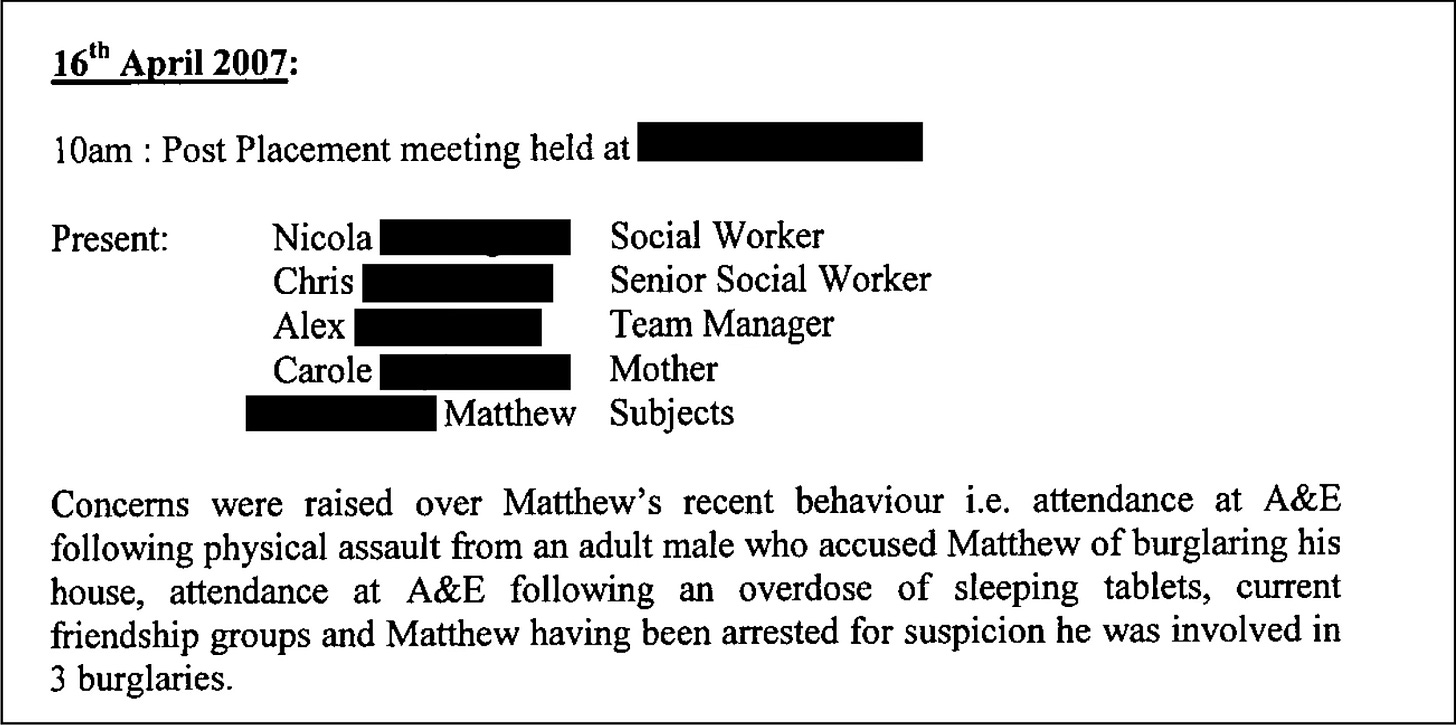

Before these two safe points, my daily summaries were pretty mundane. My fingers got tired of scrolling through many pages of “MT seems in good spirits”, and “MT up early and ready for school”. In a separate document, I found a readout from a meeting with senior social workers and care staff where they discussed whether I still needed to be looked after. They concluded it was probably time for me to go home. But my descent was in place, and weeks later, my crazy weekend or their suicide attempt happened.

I didn’t know this at the time. Now, I can’t help but think what would’ve happened if one or both requests were given. If the social workers had done what the policy set out and allowed me to participate in reasonable activities that other children my age could have. One thing is for sure, I definitely felt like I was pushed into it, not pulled, attracted, or drawn into it as they would have you believe.

Thanks for getting to the end of this piece, and I hope you enjoyed it. I’m developing this Substack channel as part of New Writing North’s A Writing Chance Programme for working-class writers. Please be a hero and subscribe to the newsletter to receive posts as they happen in your inbox. Paying is optional.

Finally, if you enjoy the writing, please help grow the channel by sharing it with your network, friends, or family. It all helps. 🙏

Yes, I see your point about the wor ''drawn'. As for the magnolia paint, please don't tell us it was also woodchip.

But seriously, it is very about time to read first hand recollections of those times & experiences.

The description of your knock on the door, in its self entertainment, is indeed evocative & quite raw really.

The magnolia paint! 🔥This is razor sharp observation and amazing writing. A fantastic read, thank you, Matt. Sophie